Africa’s architectural heritage is as diverse as its cultures, climates, and histories. From the mud-brick mosques of Mali to the intricately carved palaces of the Ashanti, traditional African architecture is a tapestry woven from centuries of ingenuity, adaptation, and artistry. Yet, in the global design conversation, African traditional architecture often occupies a peripheral space, overshadowed by Western modernism and East Asian aesthetics. This article explores why Africa’s architectural legacy is underappreciated, the richness it offers to contemporary design, and the ways it could reshape the global architectural narrative.

1. The Richness of African Traditional Architecture

When discussing African architecture, the term “traditional” is often misunderstood. It is not static or primitive; it is dynamic, adaptive, and sophisticated. Across Africa, local materials—mud, timber, stone, palm leaves—were transformed into structures that responded brilliantly to the environment and social needs.

1.1 Material Innovation

Consider the iconic Great Mosque of Djenné in Mali. Constructed from sun-baked mud bricks, it is rebuilt every year in a communal festival known as Crepissage. This method ensures both durability and environmental harmony, showcasing an intimate understanding of materials. Similarly, the Himba homesteads in Namibia utilize red clay mixed with cow dung, creating walls that naturally regulate temperature—a principle modern architects call passive cooling.

1.2 Spatial Ingenuity

African communities often design spaces around social interaction and communal living. The compound houses of West Africa cluster homes around a central courtyard, fostering cohesion and security. These spatial arrangements are not only practical but culturally symbolic, reflecting values of kinship, hierarchy, and communal responsibility.

1.3 Environmental Adaptation

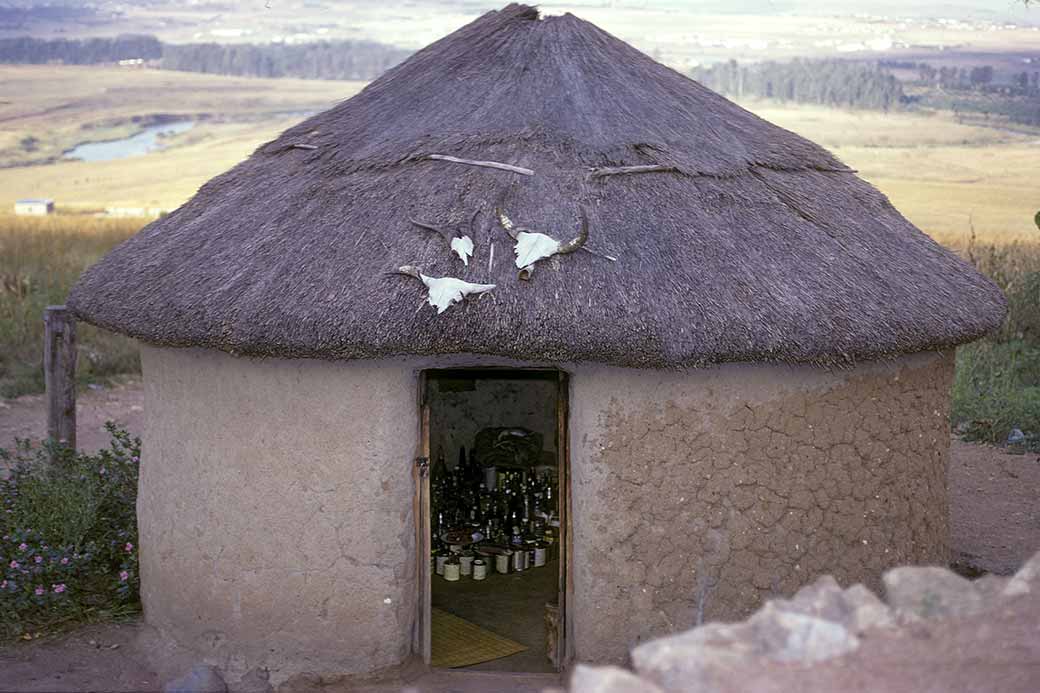

Many African structures demonstrate a profound understanding of environmental sustainability long before the term existed. In the Tata Somba dwellings of Benin, buildings are oriented to maximize airflow and minimize heat, using thick walls and ventilated roofs to create cool interiors in hot climates. Similarly, the Zulu beehive huts leverage conical shapes to shed rain and resist high winds. These examples reveal an architectural philosophy deeply intertwined with nature, yet largely overlooked in global discourse.

2. The Aesthetic Brilliance of African Architecture

African architecture is visually compelling. Its beauty lies not only in decoration but in the harmony between form, function, and symbolism.

2.1 Sculptural and Symbolic Forms

From the carved wooden doors of Ghanaian palaces to the geometric mud reliefs of Mali’s Sudano-Sahelian mosques, African buildings often serve as storytelling devices. Patterns and motifs communicate spiritual beliefs, social status, or historical narratives. Unlike purely ornamental design, these aesthetics are integrated into the very structure, blurring the line between art and architecture.

2.2 Rhythm and Repetition

Many African structures employ rhythmic repetition, a principle also celebrated in contemporary design but often stripped of its cultural significance. For instance, the repetitive triangular motifs in Nigerian Hausa architecture create visual coherence while symbolizing continuity and community. Similarly, the roundness of Rondavels in Southern Africa embodies unity and protection, turning geometry into cultural expression.

3. Global Underappreciation

Despite its richness, African traditional architecture remains underrepresented in global design discussions. Several factors contribute to this marginalization.

3.1 Colonial Legacy

Colonial histories have left a lasting imprint on perceptions of African architecture. European colonizers often dismissed indigenous building methods as “primitive,” privileging stone and brick over mud or timber. This perspective seeped into architectural education and global discourse, creating a hierarchy that still undervalues traditional African forms.

3.2 Lack of Documentation

Unlike Western architectural traditions, much of Africa’s architectural knowledge has been transmitted orally or through practice rather than formal texts. As a result, African architecture has been less documented, studied, and archived, making it less accessible to global designers and scholars.

3.3 Misconceptions About Modernity

Global architectural trends often equate modernity with glass, steel, and concrete. African traditional architecture, with its natural materials and vernacular techniques, is frequently perceived as backward rather than innovative. Yet, these methods often embody principles that contemporary architects strive to achieve: sustainability, resilience, and climate responsiveness.

4. Lessons for Contemporary Architecture

Despite underappreciation, African traditional architecture holds lessons that are increasingly relevant in today’s world.

4.1 Sustainability and Local Materials

Modern architecture faces growing pressure to reduce carbon footprints. Traditional African structures, made from local, renewable materials, offer models for environmentally conscious design. Mud bricks, bamboo, and thatch are not only sustainable but thermally efficient, demonstrating principles modern architects struggle to replicate with industrial materials.

4.2 Community-Centered Design

Many African architectural forms prioritize communal living over individualism. Courtyards, shared roofs, and cluster arrangements encourage social interaction and collective responsibility. In an era of urban isolation and fragmented neighborhoods, these principles offer invaluable insights.

4.3 Climate-Responsive Design

With climate change intensifying, passive cooling and ventilation are critical. African vernacular architecture has long mastered these techniques. The round huts of the Sahel, the tall walls of Ethiopian highlands, and the raised floors of riverine communities all demonstrate advanced environmental adaptation. Modern architects increasingly seek to integrate these principles, highlighting African architecture’s forward-thinking relevance.

5. Case Studies: African Architecture in Global Design

Some contemporary architects are beginning to draw inspiration from Africa’s traditional forms, though often without fully crediting their origins.

5.1 Francis Kéré

Burkinabé architect Francis Kéré combines traditional techniques with modern design. Using local clay and sustainable methods, Kéré creates schools and community centers that echo indigenous forms while addressing contemporary needs. His work illustrates how African principles can influence global design, yet it remains relatively niche in mainstream architectural discourse.

5.2 Diebedo Francis Kéré’s Gando Primary School

Constructed using locally sourced clay and timber, the Gando Primary School in Burkina Faso exemplifies how traditional knowledge can meet modern demands. Its design ensures natural cooling, structural resilience, and cultural resonance—a template for climate-responsive architecture worldwide.

5.3 Global Influence

While Africa’s architectural motifs occasionally appear in luxury resorts or design exhibitions, this often borders on aesthetic appropriation rather than genuine integration. True appreciation involves studying underlying principles, not merely borrowing superficial forms.

6. Challenges and Opportunities

6.1 Urbanization and Modern Pressures

Rapid urbanization threatens traditional practices. Mud houses give way to concrete blocks, and communal compounds are replaced by high-rise apartments. Without conscious preservation, centuries of accumulated knowledge risk being lost.

6.2 Educational Gaps

Architectural curricula in Africa and globally often emphasize Western techniques, sidelining indigenous methods. Bridging this gap requires documenting, teaching, and celebrating traditional forms as sources of innovation.

6.3 Global Recognition

The challenge is not merely awareness but integration. African traditional architecture should be a source of inspiration, not exoticization. Exhibitions, collaborations, and cross-cultural design projects can elevate its visibility, ensuring it informs global architecture with authenticity and respect.

7. The Way Forward

African architecture’s underappreciation is not inevitable. With deliberate effort, it can occupy a prominent place in global design conversations.

7.1 Preservation and Documentation

Initiatives to document vernacular architecture—through photography, 3D scanning, and oral histories—are vital. Digital archives can preserve intricate designs and techniques, making them accessible to global architects and scholars.

7.2 Integrative Design

Contemporary architects should move beyond mere stylistic borrowing. Integrating African architectural principles—passive cooling, communal layouts, symbolic ornamentation—into modern projects can produce environmentally sustainable and socially meaningful structures.

7.3 Cultural Exchange

International design forums can actively include African architects and scholars, fostering genuine dialogue. The global architectural community benefits not from tokenism but from recognizing Africa’s traditions as intellectually and aesthetically rigorous.

8. Conclusion

Africa’s traditional architecture is a treasure trove of innovation, beauty, and wisdom. Its underappreciation stems from historical biases, lack of documentation, and narrow definitions of modernity. Yet, it offers vital lessons for sustainability, community-centered design, and climate adaptation—principles that are increasingly essential in contemporary architecture.

Recognizing and integrating African architectural knowledge is not just a matter of cultural justice; it is an opportunity to enrich global design with forms that have endured, adapted, and thrived for centuries. By looking beyond superficial aesthetics and understanding the underlying ingenuity, the global design community can unlock a wellspring of ideas that are both timeless and urgently relevant.

Africa’s architectural heritage deserves more than admiration—it demands participation, study, and creative integration. Its future lies not only in preservation but in shaping the next generation of architecture worldwide.