Africa’s political landscape today is a rich tapestry woven from centuries of history, conflict, colonization, resistance, and resilience. To understand why political systems, governance structures, and social dynamics in Africa take the shapes they do today, one must look through the lens of its historical journey. Africa’s past is not a monolith; it is a complex interplay of indigenous civilizations, external interventions, ideological battles, and the lingering shadows of colonialism. Every political decision, reform, and upheaval carries echoes from centuries past.

Ancient Civilizations and Their Enduring Influence

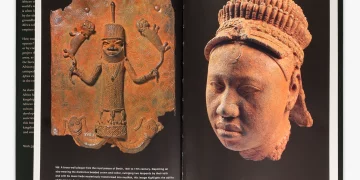

Long before the colonial era, Africa was home to some of the world’s most advanced civilizations. Egypt’s centralized bureaucracies, Kushite kingdoms, and the rich trade empires of Ghana, Mali, and Songhai established intricate political and economic systems. These societies demonstrated sophisticated governance models, legal codes, and systems of taxation, which created a sense of centralized authority and collective responsibility.

The Kingdom of Axum, in modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea, exemplifies early statecraft with its structured administration and international trade networks. Similarly, the city-states of the Swahili Coast, stretching from Mozambique to Somalia, showcased decentralized governance, where trade guilds and merchant councils held political sway alongside local rulers. These historical structures laid early frameworks for political organization, urban planning, and civic identity.

Even today, traces of these early governance models persist. Countries like Ethiopia maintain a sense of historical continuity that bolsters national identity, while the decentralized governance traditions along the Swahili Coast can be seen in contemporary practices of local councils and community-based decision-making in parts of East Africa.

The Arab and Trans-Saharan Influence

Between the 7th and 16th centuries, the expansion of Islam and trans-Saharan trade significantly shaped political institutions in Africa. Islamic scholars and leaders introduced new forms of governance, legal systems, and economic integration. The Sultanates of West Africa, such as Kanem-Bornu and Sokoto, merged Islamic law with indigenous customs, creating hybrid political structures that emphasized justice, trade regulation, and social welfare.

This period also fostered a transcontinental exchange of ideas. Political legitimacy became closely tied to religious authority, a trend that continues to influence modern politics in parts of North and West Africa. In contemporary Nigeria, for instance, political debates often reflect the historical interplay of religious and secular authority. Similarly, in Mali, leaders frequently draw upon the legacies of historic Islamic empires to legitimize governance practices.

European Colonization and the Arbitrary Borders

The most profound and enduring impact on Africa’s political landscape came from European colonization during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 carved Africa into territories with almost complete disregard for existing ethnic, linguistic, or cultural boundaries. These arbitrary borders forced diverse groups into single administrative units, creating political fault lines that persist today.

Colonial powers imposed centralized authority, often concentrating power in the hands of a few administrators who were loyal to the colonizers rather than local populations. Traditional leadership structures were either co-opted or dismantled. This pattern created governance models that were hierarchical, extractive, and heavily dependent on external authority. The consequences of these arrangements remain visible in the political fragility of many postcolonial states.

For example, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, colonial exploitation of resources under Belgian rule left a weak institutional foundation and fostered a culture of resource-driven conflict. In contrast, settler colonies like South Africa developed deeply entrenched racial hierarchies that continue to influence political representation, economic access, and social cohesion.

Independence Movements and the Quest for Self-Governance

The mid-20th century saw a wave of independence movements across Africa. Leaders like Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana, Jomo Kenyatta in Kenya, and Patrice Lumumba in Congo fought not only for sovereignty but also for a new political identity free from colonial subjugation. These movements were influenced by anti-colonial ideologies, Pan-Africanism, and global geopolitical shifts, particularly the Cold War.

The euphoria of independence often masked the challenges of nation-building. Newly formed states inherited colonial borders and centralized bureaucracies ill-suited for the social realities on the ground. Many leaders adopted a strongman approach, believing that centralized authority was necessary to hold diverse nations together. While some countries managed peaceful transitions, others, like Congo, quickly descended into civil strife, setting precedents for post-independence political instability.

Postcolonial Governance and the Struggle for Stability

After independence, Africa’s political landscape became a canvas for experimenting with governance models. Countries oscillated between democracy, one-party states, military rule, and authoritarian regimes. These oscillations were often shaped by historical trajectories: nations with strong precolonial centralized states, like Ethiopia or Rwanda, leaned toward hierarchical governance, while regions with decentralized precolonial societies, like Nigeria or Somalia, struggled with federal or local governance models.

The Cold War also left a lasting imprint. Superpowers provided military and economic support to regimes that aligned with their interests, exacerbating internal conflicts. Proxy wars, coups, and foreign-backed interventions became commonplace, entrenching cycles of instability that are still evident in regions like the Sahel and the Horn of Africa.

Ethnicity, Identity, and Political Fragmentation

Ethnic and tribal affiliations, often manipulated by colonial powers through “divide and rule” tactics, continue to shape political behavior. In many African countries, political loyalty is intertwined with ethnic identity. Electoral competition frequently mirrors historical divisions, sometimes leading to tension or violence.

Yet, ethnic identity is not inherently destabilizing. In several contexts, it provides social cohesion, mobilizes communities for development, and preserves cultural heritage. The challenge arises when historical grievances, amplified by weak institutions or external interference, intersect with political competition. The Rwandan genocide, Nigerian political crises, and conflicts in Sudan are stark reminders of how history, identity, and politics can collide destructively.

Economic Legacies and Political Consequences

Colonial economic policies were designed to extract resources rather than build sustainable economies. Infrastructure was geared toward export-oriented sectors, creating uneven development. Post-independence, many countries inherited economies highly dependent on a single commodity or export market. This structural vulnerability has significant political implications. Resource wealth can fuel corruption, entrench elites, or trigger conflicts over control of natural assets.

Countries like Angola and Nigeria demonstrate how resource abundance can both empower and destabilize governance. Conversely, nations that managed to diversify early, such as Botswana, show that historical awareness and deliberate policy choices can yield more stable political systems. Economic structures, rooted in history, continue to dictate political bargaining power, social equity, and citizen expectations.

The Role of Regional Organizations

Africa’s modern political landscape is also shaped by regional cooperation and collective memory. Organizations like the African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) are attempts to mitigate historical fragmentation and external exploitation. Their interventions in conflict resolution, peacekeeping, and democratic governance reflect a historical understanding of the continent’s vulnerabilities and the need for collective resilience.

These organizations often draw upon shared historical experiences—colonialism, liberation struggles, and pan-African ideals—to frame policies and foster unity. While effectiveness varies, the very existence of these bodies illustrates how Africa’s history informs its contemporary political architecture.

Urbanization, Migration, and Social Dynamics

Historical patterns of migration, trade, and settlement continue to shape political dynamics. Colonial cities became administrative hubs, concentrating power and creating social hierarchies that persist in urban governance. Rural-urban migration, a legacy of economic centralization under colonial rule, has contributed to political pressures in cities, influencing policy priorities, electoral outcomes, and civic engagement.

Moreover, diasporic connections, shaped by historical displacement and labor migrations, influence politics through remittances, transnational activism, and cultural exchange. African leaders increasingly navigate both domestic constituencies and global diasporic networks, reflecting the intertwined legacies of history and globalization.

Contemporary Challenges and Historical Echoes

Many of Africa’s contemporary political challenges—corruption, weak institutions, insurgencies, and contested elections—cannot be divorced from historical context. Weak institutions are often rooted in colonial-era administrative designs. Insurgencies sometimes reflect historical marginalization or unresolved conflicts over resources and identity. Political corruption can be traced to the extractive governance models established by external powers.

Yet history also provides a source of resilience and innovation. African societies have long traditions of negotiation, conflict resolution, and communal governance. Grassroots movements, civil society organizations, and digital activism are contemporary expressions of these historical strengths, adapted to new challenges.

Toward a Historically Informed Political Future

Understanding Africa’s political landscape through the lens of history allows for a nuanced perspective on reform and development. Effective governance strategies must account for historical patterns of authority, social cohesion, and economic structures. Policies that ignore historical legacies risk repeating past mistakes, while approaches informed by history can foster sustainable stability.

For example, decentralization efforts in countries like Kenya and Nigeria reflect attempts to reconcile historical decentralized governance traditions with modern state structures. Similarly, resource management reforms in Ghana and Botswana are informed by historical lessons on equitable distribution and state oversight. Recognizing the past allows African nations to craft policies that are culturally resonant, socially inclusive, and politically pragmatic.

Conclusion

Africa’s history is the invisible hand guiding its political present. From ancient empires to colonial disruption, from independence struggles to modern governance experiments, every phase has left indelible marks on political institutions, social structures, and collective consciousness. Contemporary political challenges are inseparable from this historical context, but so too are the opportunities for innovation, resilience, and unity.

The continent’s political landscape is not merely a product of immediate circumstances; it is a living archive of human endeavor, adaptation, and survival. To engage with African politics today is to read the echoes of centuries past—lessons that, if heeded, can guide the continent toward a more stable, inclusive, and dynamic future.