Global justice.

A phrase that appears in policy papers, moral philosophy seminars, political speeches, and even social-media activism threads. It sounds grand, urgent, and necessary—but also strangely slippery. Ask ten people what it means and you’ll likely get ten different answers. For some, global justice is about ending poverty. For others, it’s about enforcing human rights. Some equate it with climate action, others with fair trade, and still others with restructuring the global economy from the ground up.

So what does global justice really mean in today’s world—a world stitched together by supply chains, fragmented by political rivalry, linked by digital platforms, driven by migration, strained by inequality, and bound to a warming planet?

This long-form exploration breaks down the idea in a clear, dynamic, and professional way—without the usual academic fog. Instead, it tries to capture global justice as a living, evolving concept shaped by moral philosophy, international law, geopolitics, economics, technology, and culture.

Let’s dive into what global justice is, what it tries to fix, why it’s so endlessly debated, and what it would look like if humanity actually embraced it.

1. What “Global Justice” Is—And Why It Refuses to Sit Still

A Moving Idea, Not a Fixed Definition

Instead of a single doctrine, global justice is best understood as an umbrella term for the consequences of one deeply simple idea:

People’s rights, opportunities, and dignity should not depend on the accident of where they were born.

But while the idea is simple, its implications are not.

Does global justice require:

– reducing huge inequalities between countries?

– reducing inequalities within countries?

– eliminating extreme poverty entirely?

– limiting state sovereignty to protect global rights?

– equalizing opportunities across borders?

– sharing climate burdens fairly?

– restructuring global trade, tech governance, migration?

– or all of the above?

Different ethical traditions—cosmopolitanism, nationalism, utilitarianism, capability theory, liberal egalitarianism—define global justice differently. But most agree on one thing:

If the world were fair, it wouldn’t look like this.

The Tension at Its Core

Global justice always balances two competing ideas:

- Every person is morally equal.

- The world is governed by states, borders, and institutions that treat people unequally.

Global justice lives in the space between these truths—trying either to reconcile them or to transcend them.

2. The Four Big Problems Global Justice Aims to Solve

Though definitions vary, global justice frameworks tend to orbit four interconnected issues:

2.1 Inequality Between Nations

The gap between rich and poor nations is not merely economic—it’s historical, structural, and political. The world’s wealthiest nations built their prosperity on industrialization, global finance, and sometimes colonial extraction. Today, poorer nations remain locked into lower-value roles in global supply chains, vulnerable to currency fluctuations, debt crises, and climate shocks.

Global justice responses here include:

- debt relief

- fair trade rules

- development financing

- technology transfer

- capacity building in education and public health

- addressing historical injustices

The question is simple: Should the global economy be redesigned so poorer countries have a real chance to thrive?

Many argue yes—others argue that redistribution undermines incentives or sovereignty.

2.2 Inequality Within Nations

Even within rich countries, wealth is increasingly concentrated in small elites. Meanwhile in middle-income and poor countries, inequality often grows with economic development. Global justice isn’t only about geography—it’s also about class, gender, ethnicity, and social access.

The global justice angle asks:

- How do international institutions prevent the powerful from capturing benefits even inside their own states?

- How do global markets affect inequality at home?

- Should global corporations bear responsibility for internal disparities?

2.3 Human Rights and Political Freedom

From refugee crises to censorship to ethnic conflict, many injustices cross borders or are ignored by states. Global justice attempts to:

- enforce basic human rights worldwide

- protect vulnerable groups

- counter authoritarian abuses

- ensure fair treatment of migrants

- hold governments accountable

But this immediately raises dilemmas:

Who gets to enforce human rights, and how?

Military intervention? Sanctions? International courts? Moral pressure?

There is no easy answer.

2.4 Global Public Goods and Shared Risks

Some problems simply do not respect borders:

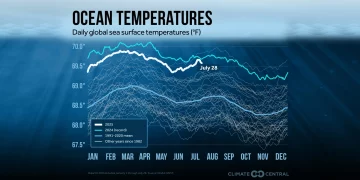

- climate change

- pandemics

- ocean health

- financial contagion

- artificial intelligence governance

- cybersecurity

- nuclear proliferation

Global justice here means shared responsibility—but also differential responsibility, since not all countries contributed equally to these problems.

3. The Philosophical Backbone: Why Global Justice Feels Morally Urgent

Even without formal treaties or institutions, there are strong ethical reasons for treating every human as deserving of fair treatment and opportunity.

Here are the major moral frameworks shaping global justice debates today:

3.1 Cosmopolitanism: The Border Doesn’t Matter

Cosmopolitans argue that every human being matters equally. National borders may be politically useful, but they have no moral justification. Every life—whether in Lagos or Tokyo—has equal worth.

This leads to strong claims, such as:

- global redistribution of wealth

- universal basic rights

- equal access to essential resources

3.2 Liberal Egalitarianism: Fairness and Opportunity

Inspired by John Rawls and expanded globally by thinkers like Thomas Pogge, this view emphasizes:

- fair opportunities for all

- institutions designed to reduce structural disadvantages

- duties of richer societies toward poorer societies

The idea is not to equalize everything, but to ensure that systemic structures do not trap entire populations in lifetime disadvantage.

3.3 Utilitarianism: Minimize Suffering, Maximize Welfare

A more pragmatic view:

If a dollar improves well-being far more in a poor region than in a rich one, global redistribution is morally required. This logic underlies many global health initiatives, development charities, and effective altruism movements.

3.4 Community and Identity Approaches

Some reject the idea of flat global equality. They argue:

- loyalties begin with community and citizenship

- states have special responsibilities to their own people

- global justice should respect cultural diversity, not impose a single model

This perspective challenges the universalist assumptions of cosmopolitan justice.

4. Global Justice in the Real World: Institutions, Imperfections, and Power

4.1 States Are Still the Primary Actors

Despite globalization, states remain responsible for:

- enforcing rights

- controlling borders

- managing economies

- providing welfare

- negotiating treaties

So even if global justice demands more cooperation, states still guard their sovereignty.

4.2 International Institutions: Necessary but Limited

Key institutions include:

- United Nations

- International Criminal Court

- World Trade Organization

- World Bank

- IMF

- regional unions like the EU, AU, ASEAN

- climate agreements

These bodies matter—but they often face:

- weak enforcement

- geopolitical bias

- uneven representation

- dependency on powerful nations’ funding

Global justice frequently runs into the hard wall of political reality.

4.3 Corporations as Global Power Players

Fortune 500 multinationals influence global justice as much as governments:

- supply chain labor standards

- carbon emissions

- data and privacy

- pharmaceutical pricing

- AI governance

- digital platform rules

Corporate responsibility is now a core part of global justice debates, especially when companies operate across borders with little accountability.

4.4 Civil Society and Bottom-Up Power

NGOs, social movements, and grassroots activism shape global justice by:

- advocating for marginalized communities

- exposing abuses

- promoting transparency

- pressuring governments and corporations

Digital activism amplifies this power, though it also raises issues of misinformation and online polarization.

5. The Five Major Dimensions of Global Justice Today

5.1 Economic Justice

This includes:

- fair trade

- ethical supply chains

- global taxation rules

- finance stability

- living wages worldwide

- universal access to essential services

Economic global justice asks: Is the global economic system fair—and if not, how should we redesign it?

5.2 Climate and Environmental Justice

The climate crisis is the clearest example of unequal responsibility and unequal vulnerability.

Global justice here requires:

- reducing emissions

- supporting climate adaptation

- financing green transitions

- protecting climate migrants

- sharing sustainable technology

It asks not only how we survive, but who pays the price.

5.3 Health Justice

Pandemics demonstrated how interconnected we are—and how unequal.

Health justice calls for:

- equitable vaccine distribution

- global disease surveillance

- universal basic healthcare capabilities

- fair allocation of medical resources

- reducing medical supply chain vulnerabilities

5.4 Digital and Technological Justice

Technology increasingly determines life chances. Global justice demands:

- bridging the digital divide

- fair AI governance

- responsible data use

- access to digital education

- cybersecurity protections

Who controls technology controls opportunity.

5.5 Migration and Mobility Justice

People move for survival, opportunity, safety, or hope. But borders restrict movement unequally.

Migration justice includes:

- humane refugee systems

- fair labor migration policies

- anti-exploitation protections

- respect for cultural identities

- shared responsibility among nations

Migration exposes the tension between moral equality and political borders more than any other issue.

6. The Hard Questions Everyone Avoids (But Global Justice Can’t)

Global justice isn’t a feel-good slogan. It raises difficult, sometimes uncomfortable questions:

- Should rich countries pay reparations for colonialism?

- Should global wealth be redistributed directly to individuals?

- Who should decide when military intervention is justified?

- Should states be allowed to restrict migration to protect cultural identity?

- Should corporations be legally liable for environmental damage abroad?

- Should climate-vulnerable countries have veto power in global climate decisions?

- Is global democracy possible—or desirable?

Part of understanding global justice is acknowledging these tensions rather than pretending they don’t exist.

7. What Would Real Global Justice Look Like?

While no one agrees on the perfect model, a practical vision of global justice today might include:

7.1 Stronger Global Rules That Are Actually Enforced

- human rights enforcement

- corporate accountability

- democratic oversight of global institutions

7.2 Fairer Economic Structures

- transparent supply chains

- progressive global taxation

- debt restructuring

- living-wage guarantees in transnational production

7.3 Climate Responsibility and Shared Sustainability

- binding emissions targets

- climate adaptation funding

- technology transfers

- transition plans for fossil-fuel-dependent workers

7.4 Universal Capabilities

Every person should have:

- education

- healthcare

- digital access

- basic security

- freedom of expression

- a chance to shape their own life

7.5 Respect for Cultural Diversity and Local Autonomy

Global justice should not flatten cultures or impose Western standards. Instead, it should allow people to pursue justice within their own traditions while preserving universal dignity.

7.6 More Equitable Global Power Distribution

This might mean:

- UN Security Council reform

- representation for small states in global negotiations

- participatory democratic mechanisms beyond nation-states

We don’t need one world government—but we need a more balanced world governance.

8. Why Global Justice Matters More Now Than Ever

Because the challenges of the 21st century are global by nature.

pandemics

climate change

AI governance

cybersecurity

financial instability

resource competition

migration

misinformation

No country—no matter how powerful—can solve these alone.

Because inequality threatens global stability.

The world’s richest 10% hold over half of global wealth, while billions lack basic services. Such inequality fuels migration waves, political resentment, radicalization, social fragmentation, and international tension.

Because global interdependence is not going away.

Supply chains, data flows, travel, digital platforms, trade networks, and cultural exchange tie humanity together. Global justice is not charity—it’s survival strategy.

Because the moral circle is expanding.

People increasingly see themselves as part of a global community. Climate activists link arms across continents. Tech workers think about global impacts. Youth movements view justice as a species-wide project.

And because the future depends on whether we can cooperate.

The next century will be defined not by dominance, but by coordination.

9. So, What Does Global Justice Really Mean?

Global justice is not a destination. It is an evolving framework for imagining and building a world where:

- basic rights are respected everywhere

- opportunities are not unfairly distributed

- the powerful are held accountable

- shared threats are addressed collectively

- cultural identities are respected

- everyone has a chance to thrive

It asks us to expand our moral imagination beyond borders without ignoring the political realities that shape people’s lives.

In its simplest form, global justice means designing a world in which being born in the “wrong” place does not doom a person’s future.

In its most ambitious form, it means reimagining the systems that govern our collective life on Earth.

And in its most urgent form, it means recognizing that global fairness is not only a moral goal—it may be the only path to a livable future.